Before Madison Holleran took a running leap off the ninth floor of a Philadelphia parking garage in 2014, ending her life at age 19, only her parents had any indication she was struggling with mental health issues. A popular track-and-field athlete at the University of Pennsylvania, Maddy, as she was known to those closest to her, appeared to be the picture of happiness and success. If Maddy was experiencing depression and anxiety—and she was, as her friends and fellow students would come to learn—she seemed to hide it well.

Before Madison Holleran took a running leap off the ninth floor of a Philadelphia parking garage in 2014, ending her life at age 19, only her parents had any indication she was struggling with mental health issues. A popular track-and-field athlete at the University of Pennsylvania, Maddy, as she was known to those closest to her, appeared to be the picture of happiness and success. If Maddy was experiencing depression and anxiety—and she was, as her friends and fellow students would come to learn—she seemed to hide it well.

That’s the thing with mental health conditions, though: they generally aren’t visible. Holleran’s reality, what she experienced every day, was virtually undetectable to others and looked nothing like the idealistic image many had of her life.

But how did it come to suicide? And what lessons can be learned from her tragic story?

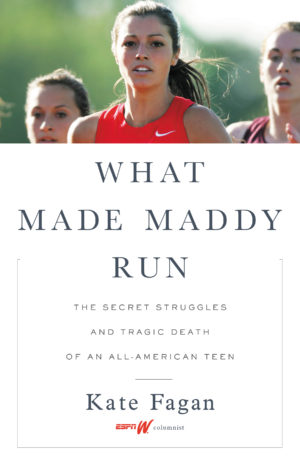

These were among the questions Kate Fagan, ESPN personality and former college basketball star, set out to answer in her book What Made Maddy Run: The Secret Struggles and Tragic Death of an All-American Teen. In an exclusive interview with GoodTherapy.org, Fagan reflects on how she came to tell Holleran’s story and discusses the importance of mental health education and awareness.

How were you introduced to the story of Madison Holleran?

I had covered the Philadelphia 76ers for three years, so I was connected to the Philly community. I remember the headlines the day after Madison died, and I think being a former college athlete and having a sister who was a former Ivy League runner, it was just a story that hit home on a number of levels.

Can you describe the process of turning your original ESPN piece on Madison, titled “Split Image,” into a full-length book?

There was really never any intention from the outset of working on that magazine piece that I thought it could be a book. I mean, to be truly transparent, mental health and a lot of the work being done in that community was not something I was familiar with when I first started on the story. Being from the ESPN world … we weren’t so much like, “Let’s really dig into the mental health aspect of this.” But the reception to it and how widely it was shared really opened the door to a lot of different conversations off of what we touched on in “Split Image.” A lot of those conversations were happening in my email inbox from students, high school and college; some athletes; some non-athletes; and some parents who had questions or who wanted to share their experiences, or who wanted to explore more the mental health aspect both on colleges and in athletic departments. So that was the catalyst for us thinking this might be something we need to tell in a longer format. And that [led to us saying], “Maybe we should turn this into a book.”

Once we decided that’s what we should do, and we had a publisher on board, and Madison’s family was on board, we knew we needed more of her voice, more understanding for the book. And her family was willing to give me her computer, which I think was essential to having that element of Madison in the story and not just the perception of Madison from her friends and family—which is of course also vital, but so much of the book is Madison’s own voice in documents she wrote, emails, texts. So I think that was a key piece in being able to expand it to this larger format. Then the other piece was Madison’s family [saying], “We don’t just want this to be Madison’s story, we feel like she’s very representative of what’s going on with a lot of young people.” So how can we make sure it’s informative, gives people good information, and touches on a lot of these cultural issues?

How did your own experiences with college sports and mental health help you with writing this book?

I think that was crucial even though—and I’m so thankful for this—I’ve never struggled with an intense kind of depression like Madison’s family feels like she obviously was dealing with at that time, a brain chemical change. I think simply understanding the kind of pressure that comes with college sports and the transition from high school to college—and I would widen that out to say that even if you’re not a college athlete the pressure in that transition from high school to college with the added academic and social pressures is something most college students can relate to. Having dealt with that and felt some of the strain in how to deal with something I thought I loved now being turned into a kind of job, and sucking of the passion away from that, I think it allowed me to relate to Madison in a way that maybe some other writers wouldn’t have been able to. And hopefully some of it crosses a universal, shared experience for not just athletes but also students who have struggled with that kind of pressure and pursuit for the kind of greatness we seem to demand of our young people these days.

Did learning more about Madison and her story help you reflect on and contextualize your own experiences in college and beyond?

Yeah, absolutely. I think I never really understood the kind of fear, isolation, and anxiety I had dealt with that freshman year of college. And it seeped into other years, but I never really understood that perhaps that was a more universal experience than I knew. I just kind of was grateful once I got past it, and it never rose to my consciousness to say, “Hey, maybe that’s an experience a lot of kids have had.” Once I had read so many of Madison’s texts and emails, talked to her friends and family, and then really dug into some of the research around anxiety and depression in young people, and then specifically some of the oral, anecdotal stories from other student-athletes, I was like, “Wow, I think this is actually something that more student-athletes are dealing with than they want to talk about.” [I tried to] turn it into a human story that other athletes of any level or other students should be able to say, “Okay, I’m not this weak failure over here while everyone else is doing great.”

Social media play a central theme in this story, mainly in that Madison used it to portray a positive, happy narrative of her life. What do you think are some positive and negative impacts of kids growing up in an increasingly digital landscape?

The positive: I think there’s that connected, instantaneous medium so when there’s an event like Hurricane Harvey, or when you need help, or when you want to be connected to someone, it’s a tool that allows you to do that in obviously unprecedented ways. And I think that can be powerful when harnessed in the right way.

But I think the flip side of that is that the connectivity can often be … exaggerated. I think we get this illusion of connectivity when we’re on Snapchat, Instagram, even email. It’s like—and I think I write this in the book—we’re in constant contact with dozens of people and yet we’re emotionally intimate with probably none of those people. Hopefully you have a few people you can lean on. When it comes to young people and developing the kind of social communication skills and the ability to be present with people, I think we’re losing some of those skills. If I was raising a kid right now, I would be really concerned [about] how we mitigate the mental effects of being so locked in.

“There are certain people who are like, ‘That’s just so dark.’ Of course. Of course it is dark. But within that statement, there’s reluctance to wade into that territory, which I think perpetuates the notion this is the unspeakable. And I don’t think it should be, because so many of us—I would venture everyone at some point in their lives—are going to deal with a mental health issue.”

Throughout the book, you share snippets of conversations you’ve had with various people about their mental health. What was it like speaking with strangers about their mental health?

I kind of entered with the myth that it would be this taboo topic, that there were un-askable questions. And I came to the conclusion I never really had to ask the questions that felt invasive. I just had to be a present, compassionate human trying to have a conversation and understand someone better. That was my main takeaway from having those conversations: asking even the simplest questions and caring about the answers, even with strangers, is all anyone really wants. People are ready to share—a lot of people, not everyone. They want people to know who they are, and they’ll share how things have truly been if they believe you’re truly interested. So it ended up not being these conversations where I felt like I was treading on doctor territory; I was just one human talking to another truly wanting to understand their experience. And I think if people approached meeting new people or friendships that way, it would go a long way toward making people feel like they had shoulders to lean on.

What are some ways our society can move toward deconstructing the stigma that surrounds mental health and seeking therapy?

I think the part that I’ve seen the most is that even occasionally in response to this book, there are certain people who are like, “That’s just so dark.” Of course. Of course it is dark. But within that statement, there’s reluctance to wade into that territory, which I think perpetuates the notion this is the unspeakable. And I don’t think it should be, because so many of us—I would venture everyone at some point in their lives—are going to deal with a mental health issue. If you’re lucky, it won’t be something that happens frequently to you, but it will happen at some point or another where, you know, you’re struggling. I think as much as we can try and not look at it like, “Oh, this is a dark corner where only professionals go” will be helpful to everyone, because I want it to be something where it can feel like not a clinical, cold conversation where only a couple of people in lab coats can have it. I want it to feel like something where there are fewer wrong steps, where it’s more like, “Be a present human for someone and you’re doing the right thing.” There’s not a lot of wrong things you can do if you’re present and you care.

How has your perception of mental health changed since you started writing about Madison and her life?

Well, this has been the most eye-opening few years for me because I never thought about mental health. I’ve been lucky enough that, for the most part, when I wake up, I’m excited. I am blessed that I’ve had only pockets of anxiety and certain panic over things, but it’s often very quarantined to an isolated challenge I’m having as opposed to something that permeates my life. And so I transferred that personal experience to the belief that’s how everyone’s mind worked. I had a conversation with someone last week who has for a very long time suffered from depression and suicidal ideation, and she always thought growing up and through her 20s that everyone woke up and struggled to get out of bed. She just thought that’s how everyone’s brain worked. So I think we all, at one time or another, until we start learning about this, feel like how our brains work must be how other people’s brains work. Once we understand mental health as being fluid, then we’re kind of opened up to wanting to learn about it and be present for people who might need us at certain moments.

Your book looks at a wide range of unique obstacles that student-athletes can encounter, especially as they enter college. What do you believe high schools, colleges, and their athletic departments can do to help make that transition easier?

There’s really functional ways that college athletic departments can help, I think. There’s some schools that institute baseline mental health Q&As, questionnaires for their incoming freshmen, so they have even the most rudimentary tool to look at if someone’s struggling a couple of months later and you give them another questionnaire and you see the change. Also, there are, in my opinion, too few athletic departments that employ full-time mental health professionals. It’s simply a resource issue of having someone in that athletic department who is there solely for the emotional and mental well-being of the student-athletes to counterbalance the number of employees and the amount of resources that go into the physical health of the student-athletes. So those are tangible [ways to help address the problem]. And then there’s just more broad, cultural issues that are going to take years to address—which is how we talk about this, you know. And those are probably decades in the remaking of being able to have better, more informed discussions that will help people feel less alone when it comes to this issue.

Help Is Out There

If you or someone you know is in crisis, please consider these options:

- Go to the nearest hospital emergency room.

- Call your local law enforcement agency (911).

- Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 (TTY: 1-800-799-4TTY).

© Copyright 2017 GoodTherapy.org. All rights reserved. Permission to publish granted by GoodTherapy.org Staff

How ‘13 Reasons Why’ Hurts: The Danger of Glamorizing Teen Suicide

How ‘13 Reasons Why’ Hurts: The Danger of Glamorizing Teen Suicide What We Mean When We Talk About Suicide

What We Mean When We Talk About Suicide Cutting and Self-Harm: Cry for Attention or Something More?

Cutting and Self-Harm: Cry for Attention or Something More?